By Mira Brody

Lonnie Ball remembers his inaugural ride up the first Challenger lift at Big Sky Resort. The two-person fixed-grip chair provided access to the razor-edge of Headwaters Ridge and expert steeps of Lone Mountain without the hike, today a feat many take for granted. Ball doesn’t—he has made the trek hundreds of times without the help of machinery.

“In 1988 when Challenger lift went in is when Big Sky really stepped on the map,” recalls Ball, a Montana native, mountain guide, firefighter, ski patroller and photojournalist who spent five decades capturing the mountain and its guests. “Challenger offered something that no other ski area in the U.S. offers—that hill that Challenger is on.”

After their first ride up the new Challenger lift in 1988, Lonnie’s wife Mary commented it was “like riding up an elevator shaft.” PHOTO BY LONNIE BALL

Lonnie and his wife Mary are considered Big Sky legends—there’s probably no corner of the mountain that hasn’t been graced by their presence. Lonnie recalls the resort’s first opening day in 1973 when he was commuting the then-dirt Lone Mountain Trail working as a forklift operator for base area construction. He watched it grow from a casual, prosaic ski hill to the Biggest Skiing in America.

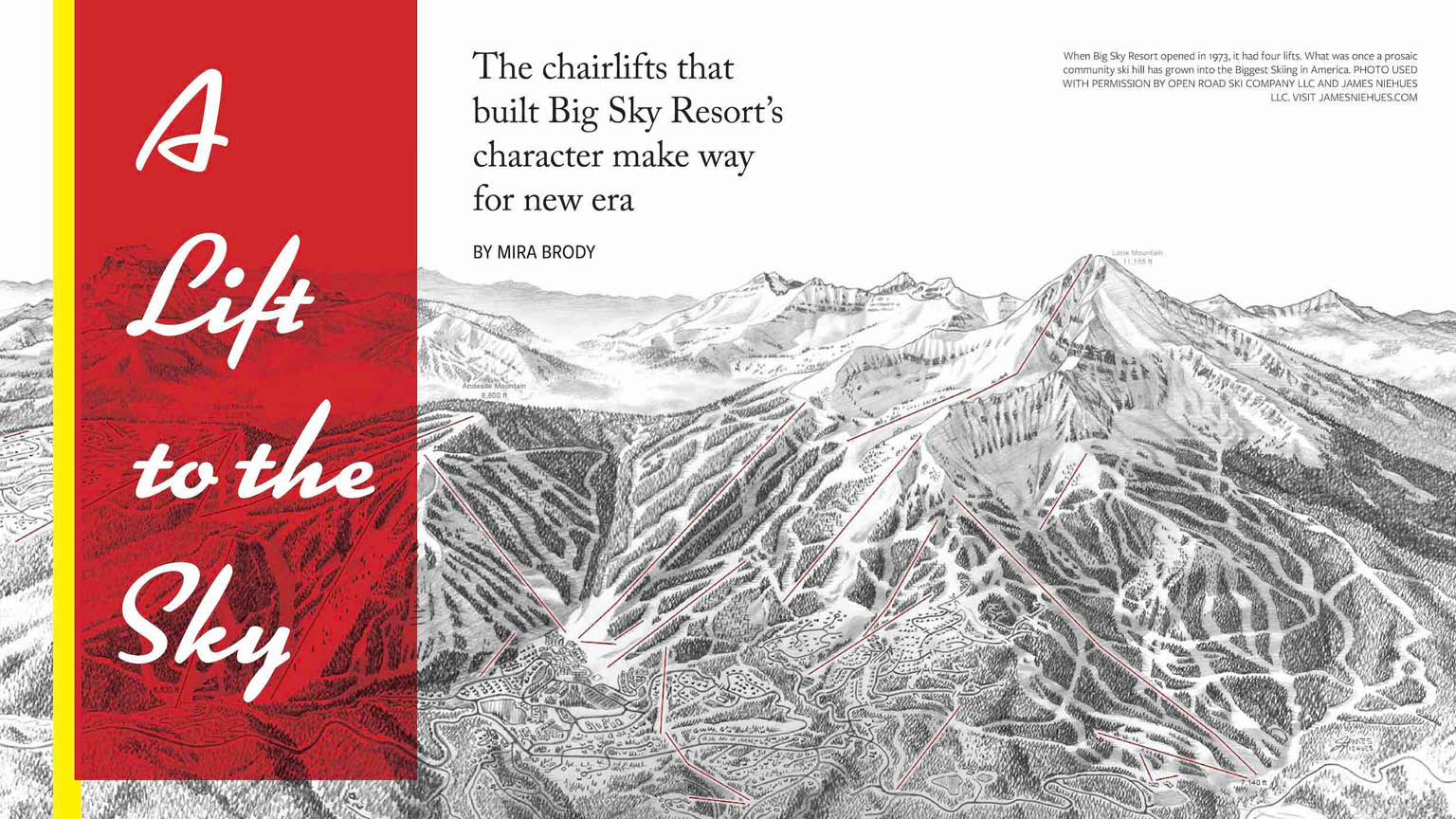

Moving skiers into previously uncharted territory on the heft of the 11,166 Lone Mountain has always been at the forefront of the resort’s vision, starting on that opening day with four lifts: Gondola I and Rams Head along with the Lone Peak and Explorer chairs. Mad Wolf was the resort’s first major upgrade in 1978—at the time the longest triple chair in the world—and expanded the ski boundary to the east side of Andesite Mountain.

For the Kirchers, though—the family who founded and own Boyne Resorts, proprietor of Big Sky Resort—innovation is in their bloodline. And it all started with a used chairlift.

First Chair

Everett Kircher, an avid skier who owned a Studebaker dealership in Detroit, Michigan, bought the land that became Boyne Mountain Resort in northern Michigan in 1947 for $1 and began building what would become the third largest mountain resort company in North America. He purchased the resort’s first chairlift, Hemlock, used from Sun Valley Resort in Idaho. It was one of the first two chairlifts ever built in the world.

When the Gondola I cabins were replaced in 2000, they were collected from all over the country and not repainted, making for a colorful display up the mountain. PHOTO COURTESY OF EVERETT KIRCHER

“What’s really unique about Boyne is that they believed from the very early days that lifts existed [to] be moved and can be reused,” said Dan Egan, a veteran skier of Big Sky’s slopes, ski instructor, writer and producer who worked closely with ski film pioneer Warren Miller. Although Egan jokes that some of this philosophy was probably due to stubbornness, it also set the stage for the Kirchers’ success.

“What their lift system did for them is to grow at a very affordable rate,” Egan continued. “Big Sky can’t afford to not be state-of-the-art because we are the state-of-the-art place to be.”

By the turn of the century, Kircher had turned his sights on the vast canvas that splayed out from under Lone Mountain’s summit and the vision that resort founder and news anchor Chet Huntley had conceptualized in 1968. In 1976, two years after Huntley passed away from lung cancer, Kircher purchased the resort from then-Big Sky Inc., and it has been a passion project of the family’s ever since, from sons John and Stephen, as well as Stephen’s son, Everett, who also inherited his grandfather’s name. At just 20 years old, Everett is currently studying business management at Montana State University and already has a desk next to his father’s in Big Sky.

By 1995, the Lone Peak Tram provided access to the mountain’s expert steeps without the hike, including the infamous Big Couloir. PHOTO BY LONNIE BALL

When talking to Everett Kircher, one can tell that, when he looks at Lone Mountain, much like the men in his family before him, he views it as a sort of algorithm, visualizing each lift route, past and present, the alignment changes over the years and the scars left behind.

“I remember when I was really little—I was seven when Gondola I was taken out—I remember that lift was always my favorite,” recalls Kircher. “I just really liked the gondolas, it’s almost like Walt Disney—a futuristic but retro feel to them.”

Despite the imposing view around him when he hikes the mountain, Kircher’s focus is on the ground. He’s traced the Gondola I route thoroughly in the warmer months, excavating pieces of old chairs, slabs of concrete and items dropped from riders past—a rusted tin of Copenhagen, Budweiser can and disposable camera, to name a few.

Gondola I (1973-2008) and Gondola II (1983-1996) sat side by side, transporting riders from the base area to Rice Bowl. When the former had its cabins replaced in 2000, they were collected from all over the country and left unpainted, making for a bright strand of bulbous cabins, stark against the white backdrop. The latter was relocated from Squaw Valley, California, and now serves as a scenic lift in Wallowa Lake, Canada. The Swift Current quad, which was removed this year, followed its alignment during its 25-year reign.

Above the Clouds

One alignment that hasn’t changed since the resort opened is the Explorer lift. Riding Explorer is a bit like traveling in a time machine. After all, the fixed-grip double chair, manufactured by Heron-Poma, has been chugging along since the beginning.

Colorful onesies make for some relaxing après in the Big Sky Resort base area. PHOTO COURTESY OF THE GALLATIN HISTORY MUSEUM

Surrounded by state-of-the-art upgrades, Explorer offers a taste for what chairlift riding was not long ago—a slow and steady climb 622 feet in elevation, being gently tousled at each of the 14 towers, a view of Lone Mountain growing in front of you and the bite of winter softened by the gentle banter of a seatmate.

“What happens from the bottom to the top, there was an experience, there was an intimacy, there was a smile, someone confided in you and it was uninterrupted by a stranger, or many times it was enhanced by the stranger who joined the lift with you,” said Egan, recalling the intimacies of the older lifts. “What’s being lost is that experience. There was more depth to the conversation.”

As part of Big Sky Resort’s 2025 vision, Explorer will join past Big Sky lifts as a mere memory when it’s replaced with a two-stage Gondola from the base area parking lot. Replacing these lifts is a component of the resort’s tradition. Before that, in 2016, Powder Seeker took the place of the Lone Peak triple; in 1996 Swift Current replaced the Gondola II, originally from Squaw Valley; in 1993 Thunderwolf replaced Mad Wolf; and the Ramcharger quad, which would later become Shedhorn 4, replaced the original Rams Head.

Cascade is originally from Crystal Mountain, Washington; Dakota was once Southern Comfort; Headwaters came from Kirkwood Mountain Resort, California; Little Thunder was once in Brighton Resort, Colorado; Lone Moose is from Keystone Resort, Colorado; and White Otter was from now-retired Conquistador Ski Area, Colorado.

Back then, it was not uncommon for chairlifts to pirouette across the mountain and country, spending their newfound home in a fresh mountainscape and loyally pulling friends, family and athletes up peaks to experience the freedom of skiing, an industry that has shaped much of the culture of what it is to live in Big Sky.

The Lone Peak Tram was a passion project of Stephen and John Kircher, who ordered the parts before telling their father. Today, it takes skiers deep into the clouds on the 11,166-foot Lone Mountain. PHOTO COURTESY OF BIG SKY RESORT

One lift that has yet to be replaced, and perhaps the most iconic of them all—is the Lone Peak Tram. To this day, it’s Ball’s favorite lift.

“I knew that first time that I rode up there and stepped onto the Tram deck that this was going to be home,” said Ball, who recalls fondly that he was able to ride the Tram before its public debut in December of 1995. Before its installation, a hike to the peak had been an annual tradition. “To be on the 11,000-foot peak—it has been incredible.”

There’s no story about Big Sky Resort’s devotion to world-class lifts without mention of the clothesline-esque, gravity-defying piece of machinery that takes riders deep into the clouds—and sometimes above them.

To John Kircher, the concept of a Tram to the pinnacle of Lone Mountain was akin to Capt. Ahab’s White Whale—something he had been dreaming of even before he took over for his father in 1979. Kircher family friend Egan recalls John ordered all the parts before gaining approval from senior Everett.

“My grandpa was afraid of heights,” Everett Kircher said of his namesake. “You’ll notice any lift that he designed, they’re not more than 15 feet off the ground, like all the lifts in Boyne, Michigan. When the idea of the Tram came up you can imagine he was not down with that kind of lift. And it was going to be expensive.”

Today, the Lone Peak Tram prevails as the resort’s crown jewel. There’s something about standing inside that cabin, the hushed quiet as you move toward the gaping headwall of Lone Mountain, taking in the timeless geographic details of its chutes and crags. That ride is just enough to remind you of your insignificance, a power that keeps people coming back.

Reaching the sky

Ball in his studio, surrounded by 50 years of ski photojournalism. PHOTO BY MIRA BRODY

The drone of a Black Hawk helicopter echoes off the surrounding mountaintops on a warm September day as it makes its way up and down Lone Mountain. With each trip, it returns to the Big Sky Resort base area parking lot to retrieve a massive, 7,000-pound steel lift tower dangling from a rope. In one of 200 or so trips, the pilot expertly maneuvers the piece of what will soon be the new Swift Current 6 chairlift—the fastest chairlift in North America—up to crews working to complete the resort’s newest amenity before opening day, Thanksgiving 2021.

When Gondola II was removed from the resort, Ball purchased two cabins in exchange for a case of beer. One of them still lives in his backyard. PHOTO BY MIRA BRODY

“I know it’s a huge paradigm shift compared to what was around before,” said Everett Kircher. “We’re in an age where Big Sky is going to get a lot of people coming and we want to be able to maintain our lack of lift lines and the experience, and we don’t want the base area to be crowded. The idea is to build these lifts to have more capacity than we will need.”

Big Sky Resort has been turning a close eye on the future, to create the most technologically advanced lift network in North America. The construction of Swift Current 6, which will include ultrawide heated seats, a blue plastic bubble shield and the capability of whisking 3,000 skiers up the mountain each hour, represents both a piece of that vision and the path they’ve paved to get here.

In his Bridger Canyon studio outside of Bozeman, Lonnie Ball pores over hundreds of slides and photographs of Lone Mountain from various decades, a visual representation of that path. His windows overlook Bridger Bowl Ski Area, the metal lifts glistening through a patchwork of yellowing leaves. Sitting on his back porch is one of the red Gondola II cabins, which Ball bought for a case of beer after they were removed from the resort.

Photographing the mountain and the people on it has been the highlight of his life, he says. He points out a photo of Erika Pankow, a Big Sky Ski Patroller who passed away tragically in 1996. There she is, standing on the ridge, surrounded by friends, smiling.

A group photo from 1995, including former Big Sky Resort ski patroller Erika Pankow (third from left). PHOTO BY LONNIE BALL

Ball pulls at another memory, one that will light up the faces of many Big Sky greats: Oly Days; grown men flailing down Andesite Mountain in rubber tubes. Oly Days was a series of inner tube races, snow sculpting, live music and a Calcutta auction, all fueled by copious amounts of Olympia beer and the collective feeling of being alive in Big Sky.

“Now a lot of people ask me how do I ski because I do have a walking disability, but when I put my skis on and I hear that ‘click, click’ of those boots, it’s like … a bird flying out of its cage,” says Ball, joking that he lived up to his nickname, “Launchy.”

“And I spent a lot of years in the air,” he adds.

Ball captured the resort’s inner tube races down Tippy’s Tumble in the March 8, 1976 issue of the Bozeman Daily Chronicle. PHOTO BY LONNIE BALL

Indeed, Ball was the first person to ever ski Jackson Hole’s infamous Corbet’s Couloir. He met Mary while patrolling at Alta Ski Area in Utah. His children and grandchildren grew up skiing the resort and he and Mary still ski more than 80 days a year. Egan, a close friend, recently nominated Ball into the U.S. Ski and Snowboard Hall of Fame. Skiing has shaped most of this man’s life.

As the area grows and changes and new lifts replace the old, many may yearn for the nostalgia of those fixed-grip lifts, gravel road, quieter lines and flailing inner tubes.

“When you say the old days of Big Sky,” Ball says, “they all blend into one single thing.”

He’s referencing memories of the mountain, the people on it and lifts that help them reach the sky.